SASAKI SHOURAKU

Region: Kyoto

Rakuyaki (raku ware) has strong ties to sadou - tea ceremony - and is one of the most famous types of ware in Japan. It is said that Sen no Rikyuu, sadou's most influencial person, asked a tile maker named Choujirou to make rakuyaki chawan suitable for his wabicha, showing a sense of rustic simplicity. The idea of wabicha heavily contrasted the use of ware made from gold or imported from overseas at that time. Technically akaraku came first, as the glaze was already readily available. All of this happened more than 450 years ago, and to date raku chawan are still seen as one of the most prestigious types of ware by tea masters.

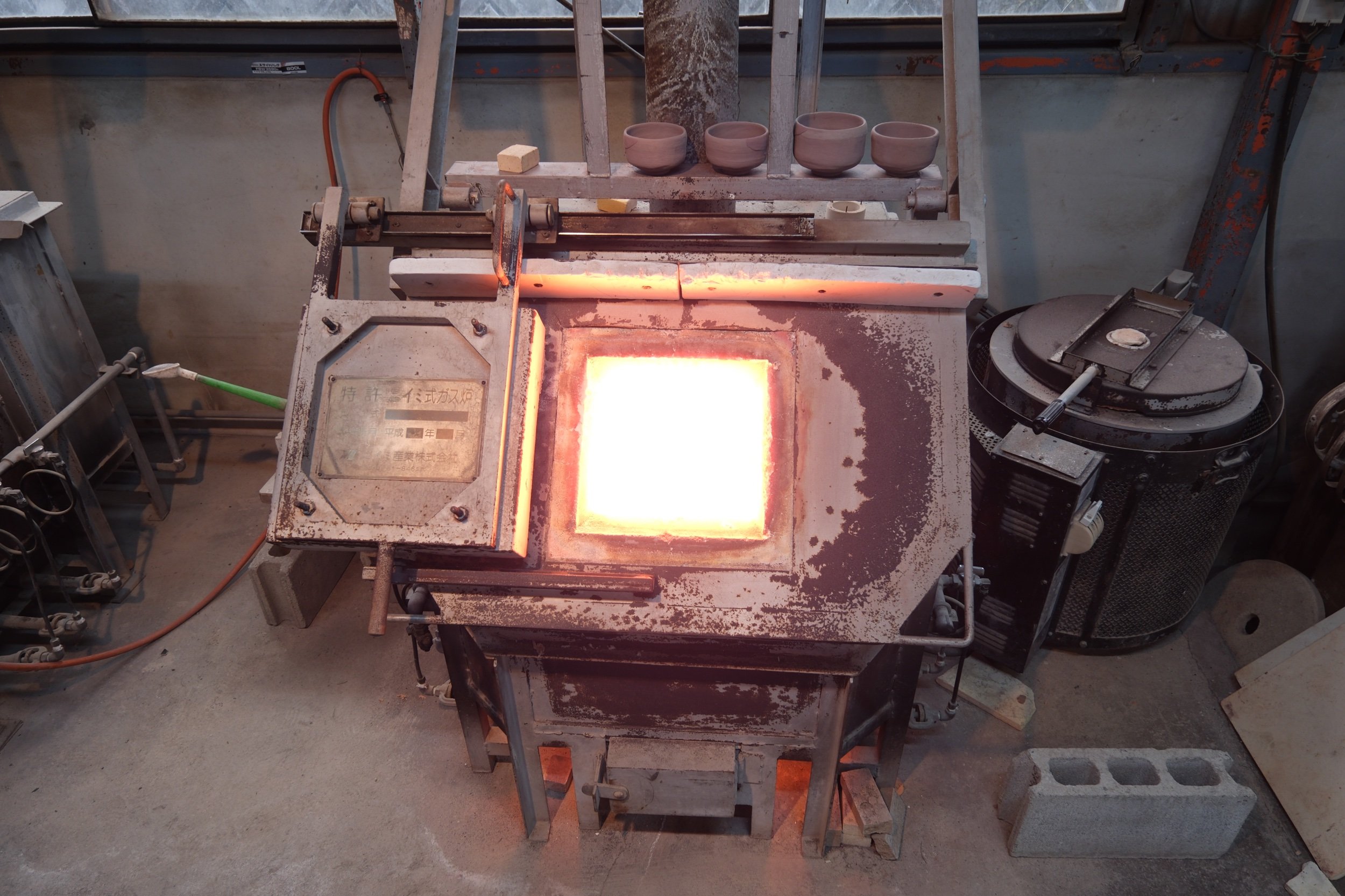

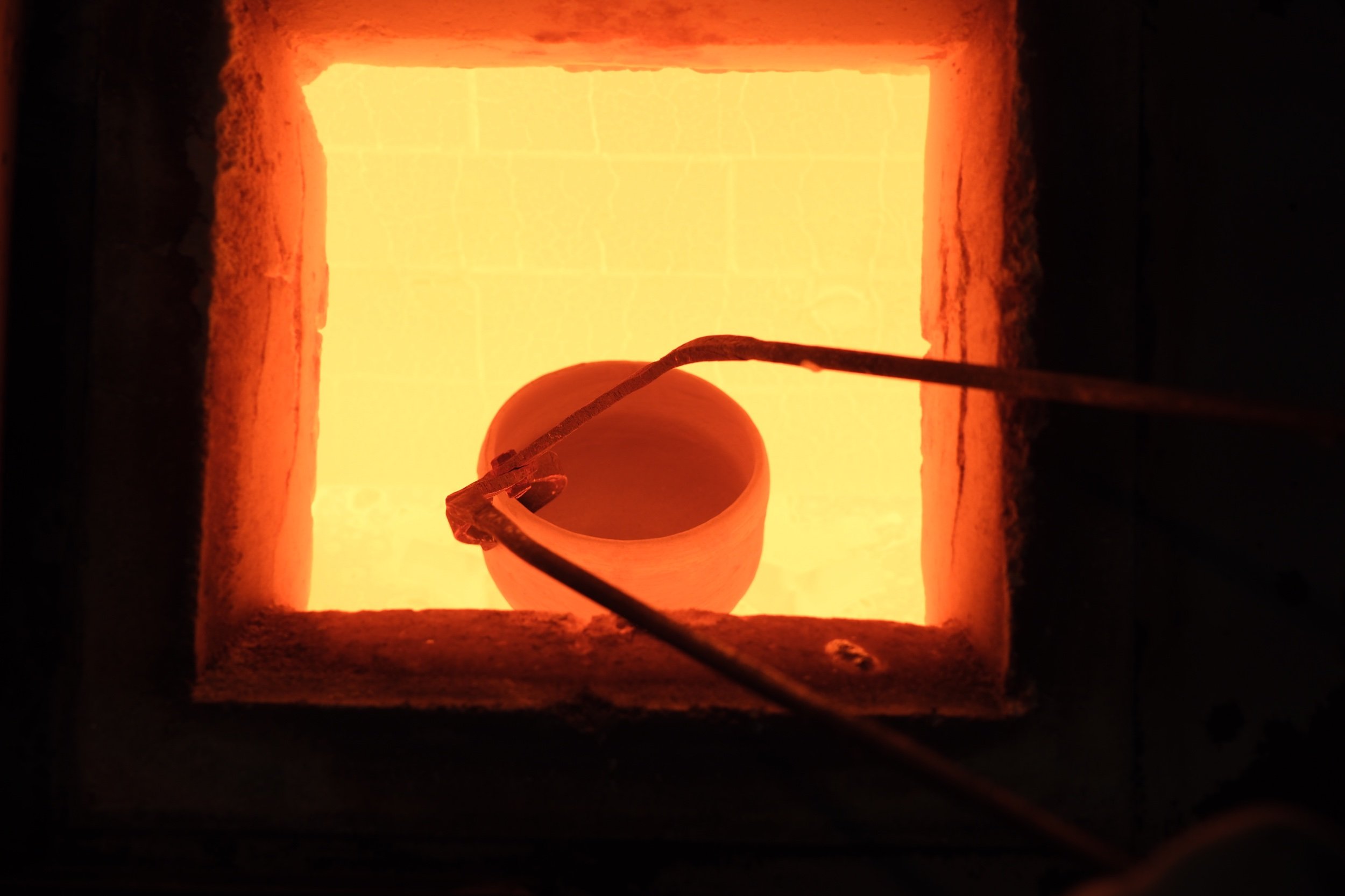

While most ware are thrown on a potter's wheel, raku chawan are made by a special hand-building technique called tezukune, in which a ball of clay is pressed into a thick disc, the edges are gradually raised by pulling bit by bit to shape a bowl that fits comfortably into the user's hands. Rakuyaki is usually divided into kuro (black) and aka (red). Kuroraku is fired at around 1200 degrees for 3-5 minutes and requires the use of a special kiln. Akaraku is fired at a lower temperature of around 850 degrees, but for a longer time and can be fired in an electric kiln.

While you may find more modern making of rakuyaki, of the traditional rakuyaki kilns there are only around 10 remaining in Japan, with 5 of those being in Kyoto. The Sasaki family is well known for their traditional making of rakuware since the opening of the kiln in 1903 and currently Sasaki Yamato is the fourth generation of this kiln. The kiln is based in the hills in Kameoka city, Kyoto.

On the day of our visit, not only did we learn more about rakuyaki, we also had the opportunity to make our own raku chawan. They are left to dry for around a week before glazing and firing. And we must say we are quite proud of our own raku chawan!